Welcome to Not Knowing How: Adoration Revisited, a capsule newsletter by Lisa Locascio Nighthawk in sixteen parts. Names have been changed. The version of events is my own.

“As a playful character Annie-Dog is like many women I’ve met and found fascinating, being among those who are willing to trade their bodies so readily for something much more valuable; like say attention, or the appearances of love.”

— Billy Corgan, Adore reissue liner notes, 2014

In college I was invited to be the student member of a search committee for a new professor. I loved poring over the CVs. Everyone impressed me, but I soon found that only a handful were actually competitive. One letter of interest enumerated its author’s research interest in “the body.” In our committee discussion, I volunteered that this detail compelled me. “Yes, but that’s very ten years ago,” a professor said gently.

That was 2005. But all these years later I am still interested.

I feed my baby at seven, lying on my side in bed or sitting up on the couch under the window in the living room. I try not to hunch over, but when it seems this is the only way my baby will settle and drink deeply, I hunch. I wash my face and brush my teeth; twice a week I wash my hair. I sit at my desk—in my bedroom now, so that the baby and the carer who watches him three days a week while I work can have the bulk of the apartment —and use my Bluetooth keyboard and mouse and plastic laptop stand, little ergonomic fixes prescribed me by my husband to make the hours of Zoom calls and emails and spreadsheet maintenance as light on my body as possible. I sit on a yoga ball chair I bought when I was pregnant to replace the tall light suede office chair in which I wrote four book manuscripts. I try not to hunch.

During the day I feed my baby his meals from my body. If I have to be on Zoom, I attach a machine to my body to extract the milk, which I pour into a small plastic bag and freeze so that his carer can thaw it and give it to him in a bottle. After the carer leaves, and whenever I get the chance, I play with my baby. I hold him in my arms, fly him through the air, show him the world outside our windows. I lie next to him on the floor and pull a pink silk scarf over our faces. I change his diapers and kiss his feet. If he is fussy and seems tired of me, I strap my baby into a mechanical swing and let it rock his body.

At 5:30 my husband straps our baby to his body, or I strap him to my body, and we go for an hourlong walk. The walk has become my favorite part of the day, something good I can do for my body, a way to take care of it, to both rest and exercise it while holding my shoulders back and up. A time when I am not peering into a lit screen. We look into the windows of apartments and schools and houses and restaurants as the sun goes down.

Back home, my body tidies while my husband gives the baby his bath, and then I lie on my side in bed again to feed my baby.

We put our baby to bed with our bodies, kissing his face, brushing our long hair against his nose so that he opens his mouth in joy, tucking and snapping and zipping his body into his heavy layered sleep sacks. Then my body does the day’s dishes while my husband cooks dinner. My body sits down to eat. After dinner my body works on this newsletter. I have recently had the insight, perhaps not particularly original, that although writing is the work of the mind, the brain, too, is part of the body. Thus writing, like all of my work, is physical labor.

I’ve started to experience a sharp, tingling sensation across my shoulderblades and in the center of my back when I use my body for too many hours without rest. I try to remember to lie down on the floor for a few minutes at the end of the night. When I get into bed I lie down on my back, but I know I won’t stay this way. My body will keep moving, even as I dream.

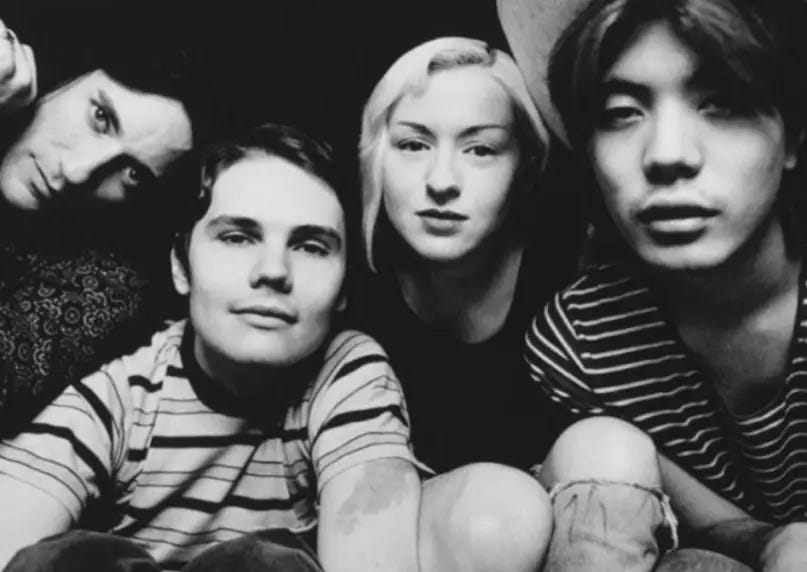

D’Arcy Wretzky is the only woman member of the original Smashing Pumpkins lineup, the only member of the band not from the Chicagoland area (she grew up, and lives today, in South Haven, Michigan), and the only one who did not yield to Billy’s call to return. When I began this newsletter, it was time, finally, for me to think about D’Arcy.

Icy cool girl bassist. Psychedelic grunge goth Hitchcock blonde. Beautiful, alluring, silent. Present for but disaffected from the aesthetic of Nineties girl power. Where Spice Girls were loud and cheerful and Hole angry and profane, D’Arcy was remote and observant. A lovely iconic image, like a tarot card, or a still from a film adaptation of a gothic Scandinavian novel.

She was mysterious, which is a word men use to describe women who keep their mouths shut.

Hers was a body at work. The work of her body was to be seen.

When I was fourteen, the coolest place I could imagine was Clark and Belmont on the North Side of Chicago, then the epicenter—at least according to my first boyfriend Jeff—of a hip goth scene. Its anchor was The Alley, an august leathers store where I bought a miniskirt in September 1999. At home, I dressed up in my new skirt with a black-and-white striped turtleneck sweater and went down into my kitchen. My dad told me I looked nice. Then he started talking about needing to be careful. I should only wear my outfit in places that were safe. Not, for example, Clark and Belmont. I was nonplussed. Of course I would wear my outfit to the place I wanted to be seen. It was my task to maximize my desirability into an announcement of my entrance into the world.

Despite what my father said that day, my parents never tried to control my outfits or my hair or my makeup. That was what school was for. When I was sent home because my skirt was too short, I returned in a corset and lace-up vinyl pants.

If there was a woman rock star I emulated, it was Courtney Love. Or Nina Gordon and Louise Post from Veruca Salt. Or Björk. Or, before I even knew who the Pumpkins were, Alanis Morrisette. Or Madonna, the goddess of my early childhood. When I imagined the band Moira and I wanted to start together, I patterned us on Love and Melissa Auf der Maur, who would replace D’Arcy after her 1999 departure from the Pumpkins. Like Moira, Auf der Maur was a Canadian bassist with a mane of long wavy hair. Like me, Courtney Love was daring and insistent and possessed a flair for the dramatic.

D’Arcy was there in every photograph of the band, the lady Pumpkin, dreamy and compelling. I liked looking at her. But I never mistook her for the main character.

When she left the band not even a year after I first heard “To Sheila” on the radio, I was bummed because a bad thing had happened to my favorite group. I didn’t think about why she did it, about what might have led her out of the Smashing Pumpkins and into an attempt at a film career in L.A., where she was photographed with Mickey Rourke, looking different.

Today D’Arcy is a frequent topic on the Smashing Pumpkins subreddit and other fan boards. Once, the fans write, she was a goth hottie with a unique look. At the height of her fame, no one was beautiful the way that she was. Her presence was magical. But she doesn’t look like that anymore. In fact, she looks scary. She’s messed up her face. She was a very attractive lady, the mugshots are terrible...

Since leaving the band, D’Arcy has been arrested for possession of crack cocaine, for a DUI road rage incident, and for letting her horses roam her rural Michigan hometown. On the boards, the Rourke pictures are reposted with a few more recent ones. Hands are wrung. The consensus seems to be that D’Arcy we remember—the D’Arcy that belonged to us—is lost forever now.

If you accept the popular notion of Smashing Pumpkins as a monarchy with Billy as divine king and the rest of the band as, at best, lesser nobles empowered only as they maintain his favor, why not value Jimmy and James and D’Arcy equally? Jimmy was kicked out of the band for his drug use and his presence at the death of its touring keyboardist, but he has been granted a triumphant redemption arc. D’Arcy’s absence haunts the band, an inconvenient reminder of another story beyond the one about the lovely young woman everyone liked to look at.

When I was a teenager, I didn’t play a sport or have chores or a regular job. I went to school and read books and had sex and watched movies and went on vacation and shopped with my mom and lay on couches talking to my friends. The brief stints I did spend employed—three months at a local bakery where the aspiring-lech manager gave me the whole tip jar at the end of every shift; six weeks one summer in a classroom of children trying to pass sixth grade math, assisting a teacher who plainly hated her students—I pursued as a rebellion against my parents. They didn’t want me to work; they wanted me to get good grades and to spend as much time with them as possible. But working is virtuous! I thought. I wanted to show them I was good.

Whether I had a job or not, my body was working. I went to breakfast alone at a diner and the manager came out to tell me what an honor it was to have “someone like you dining with us.” Waiting for a train, I was approached by a man who asked for my phone number in a lilting lisp and called me a bitch when I declined to give it. I stood, tossing my hair out of my face after locking up my bicycle in front of the bakery where I worked, and a boy in the uniform of the local Catholic high school stopped in his tracks to ask me to coffee. He was polite, but he also wouldn’t leave me alone until I said I had a boyfriend. As I walked away from him at the end of the last night of the week we spent writing poetry together in a college dorm, the friend I made at the youth program run by the National Foundation for the Advancement of the Arts called “You got a nice ass!”

I was confused. I was just hanging out, being myself. I wasn’t courting their attention. But my body did not exist in a vacuum.

In 2018, when I wasn’t paying attention to the Pumpkins at all, D’Arcy turned screenshots of her text conversations with Billy over to the press. He’d invited her to join the band on its reunion tour, to come back as James was coming back, and then whittled away at his offer, she said, until it became clear that he had no intention of letting her actually play bass on tour. For that, he had already acquired the services of Jack Bates, the son of Joy Division co-founder Peter Hook.

The texts are awkward to read, both because her screenshots of their conversation are obviously selective—things have been left out—and because of the tired familiarity on display. He’s worried about money—D’Arcy claimed that Billy shared that his investment in his National Wrestling Association put him in a bad spot financially—and says they will never be able to tour in Europe unless they play perfectly at these upcoming shows. D’Arcy makes reference to an injury, says doesn’t want to be rude to her mom by texting, but that she’s excited to talk with him more. What begins as a polite conversation grows more miserable with each text. D’Arcy becomes more taciturn and Billy more agitatedly verbose. These two people who once knew each other well, whose fortunes remain intertwined: their fractious exchange is made more painful by their obvious intimacy.

The public feud occasioned a lengthy interview in which D’Arcy shared her memories of her time as a member of the Smashing Pumpkins.

“I had a miscarriage because of the stress. Nobody knows that, except for my sister and Kerry Brown, my ex-husband. The band doesn’t know that, nobody knows that. The stress was so much that I had a miscarriage. It was very traumatic. […]

I was going through a really bad time, I didn’t know what was happening, I was having a nervous breakdown. I had 30 plus panic attacks a day, I didn’t know what it was, it was terrible. The day after the tour, I had tried to quit two or three times, but it’s difficult to do when you have everybody, my husband, my family, telling me, ‘No, no, just wait until the next record. All of these people are depending on you, all of these people who work for you guys, don’t just think of yourself.’ I just should have left a couple of years earlier. […]

You know how they’re always telling you in school drugs will do this to you; they’ll do that to you, drinking kills your brain cells? At the time I was like good, maybe I can kill off all these horrible memories, because I have night terrors, panic disorder, you name it. I was like; I’m going to see if I can’t kill those brain cells off! I wouldn’t recommend it, it didn’t work. I count myself lucky to be alive.”

Whenever a picture surfaces of D’Arcy as she is now, the fans who loved her when she was young are aghast at her lip augmentation. (Inevitably, someone will post an old photo in which they think she "looks really happy” in response to a contemporary image of D’Arcy.) In their discourse, her face has become its own mirror scare, with a whole subplot orbiting a “horrific picture” (as it is always called) of her bruised and bloody face that was posted in 2018 by odious Q101 radio host troll Mancow and has since been referred back to as proof that D’Arcy was unwell, not in her right mind, and this was why she was fighting with Billy.

It is not hard for me to understand why D’Arcy would change the way she looks. The body works until it encounters an obstacle in its work, and then it tries to find a workaround.

Some years ago I was a candidate for a position at a university in a city I’d never visited. The school flew me out for an interview that lasted three days. As she was driving me from one event to another, a professor took me aside and said, “I think they’re going to offer you this job, and I just want you to really consider taking it. It’s not New York or L.A. But you can have a great life here.”

That was exciting. But I was not surprised when I didn’t get the job. Almost no one gets the job.

That evening, a different professor drove me back to my hotel, and when we got there, he asked if I wanted to have a drink. It seemed safe, innocuous: we were talking about his child. Then he was looking me up and down, talking about my body. The next day, he was aggressive with me throughout my teaching demonstration, attacking everything I said, rolling his eyes, sighing in exasperation as I spoke.

Or maybe I imagined all of this. It’s very hard to get a tenure-track job. I should know: over the course of five years, I was one of two finalists for twelve assistant professorships I was not offered.

I filed the experience away until the fall of 2017, when the Me Too movement inspired me to report it to the department that had interviewed me. All I wanted was for a note to be made somewhere, so that if a student reported a similar hostile experience with him, those charged with resolving the matter could see that there was precedent. I wrote to the professors who had kindly guided me around campus during my visit, including the one who had told me she thought I would be offered the job.

The impersonal and brief reply I received referred me to a pair of administrators who stonewalled me for months. Finally they interviewed me in an odd, self-congratulatory tone, telling a long story about how they had hired a woman who was eight months pregnant into a senior position. Months later, I received an email with their final report. Something told me not to read it, so I marked it as read and moved on.

It wasn’t until more than a year later, when I was speaking on the phone with a graduate student in psychology to whom I had agreed to talk about my experience reporting sexual harassment in the workplace, that I opened the email. When I saw what it said—that my drinking worried the faculty members who met me, that I shared inappropriate and intimate details of my personal life with the women faculty with whom I recalled sharing a wonderful lunch, that everyone was made uncomfortable by my behavior—I started crying and couldn’t stop. I couldn’t explain myself, except to say, over and over, “My career is the most important thing to me. I would never—I couldn’t—This isn’t true—You don’t understand—I’m not like this—”

It is safer to be that image that is desired and disdained and forgotten than to speak and become real.

Thank you for reading! This is the eleventh of sixteen installments of Adoration Revisited, which will be released every Friday between December 2, 2022 and April 7, 2023, or whenever it’s done. If you enjoy my newsletter, I’d be honored if you share it with your friends. And I’m always interested to hear about your obsessions and memories.

This was very weird, it seems inappropriate to shoehorn yourself into a story about another person, or to shoehorn news about another person into your personal blog. I hope you don't consider this reporting.