Once Upon A Time

Adoration Revisited, part five

Welcome to Not Knowing How: Adoration Revisited, a capsule newsletter by Lisa Locascio Nighthawk in sixteen parts. Names have been changed. The version of events is my own.

Like 'For Martha,' it was penned in direct opposition to my Mother's untimely death. A message I suppose for things I would have like to have said, but didn't have the courage for. A personal highlight, and one I treasure regardless of current taste or favor. The purest of them all.

— Billy Corgan’s notes on “Once Upon A Time” from the 2014 Adore reissue

I loved the Pumpkins for their music. For their words and sounds, for their faces and bodies, for what I believed were their souls. I loved them not in spite of, but for, their oft-mocked qualities: the sour tang of Billy’s voice, the high melodrama of his lyrics, his perpetual bad attitude. (Did being his fan make me more like Billy, or did I become his fan because we were already similar?) Everything about the Pumpkins moved me, made me feel seen, made me want to listen to their albums over and over.

But I also loved the band because, like me, the Smashing Pumpkins were from Chicagoland. (My dad, a born and bred Chicagoan who emanates the spirit of the place through his pores, hates that I love this car commercial word. But I do. It contains within it the suburbs where I lived the beginning of my life and the city that we orbited, a perfect crashing-together.) My home was their home, woven into their mythos and history. Billy grew up in Glendale Heights, James in Elk Grove Village, Jimmy in Joliet. D’Arcy was from South Haven, Michigan, up along the curve of the lake. They met and worked and lived still in the city I visited often, just twenty-five minutes drive away on 290.

Before the Pumpkins, I already loved Chicago. Living in the suburbs during the 1990s Bulls championship run had imbued me with local pride. Watching a television program that began with aerial footage of downtown set to the team’s iconic theme, tears sprang to my eyes, an experience I tried to describe to my father, who later wrote me a letter about how he felt the same way. The Smashing Pumpkins felt ineffably familiar to me, the ideal soundtrack to my life in the home we shared. I felt the famous lyrics from “Tonight, Tonight” in my heart:

And the embers never fade

In your city by the lake

The place where you were born

Live, Billy often sings it as “my city by the lake.”

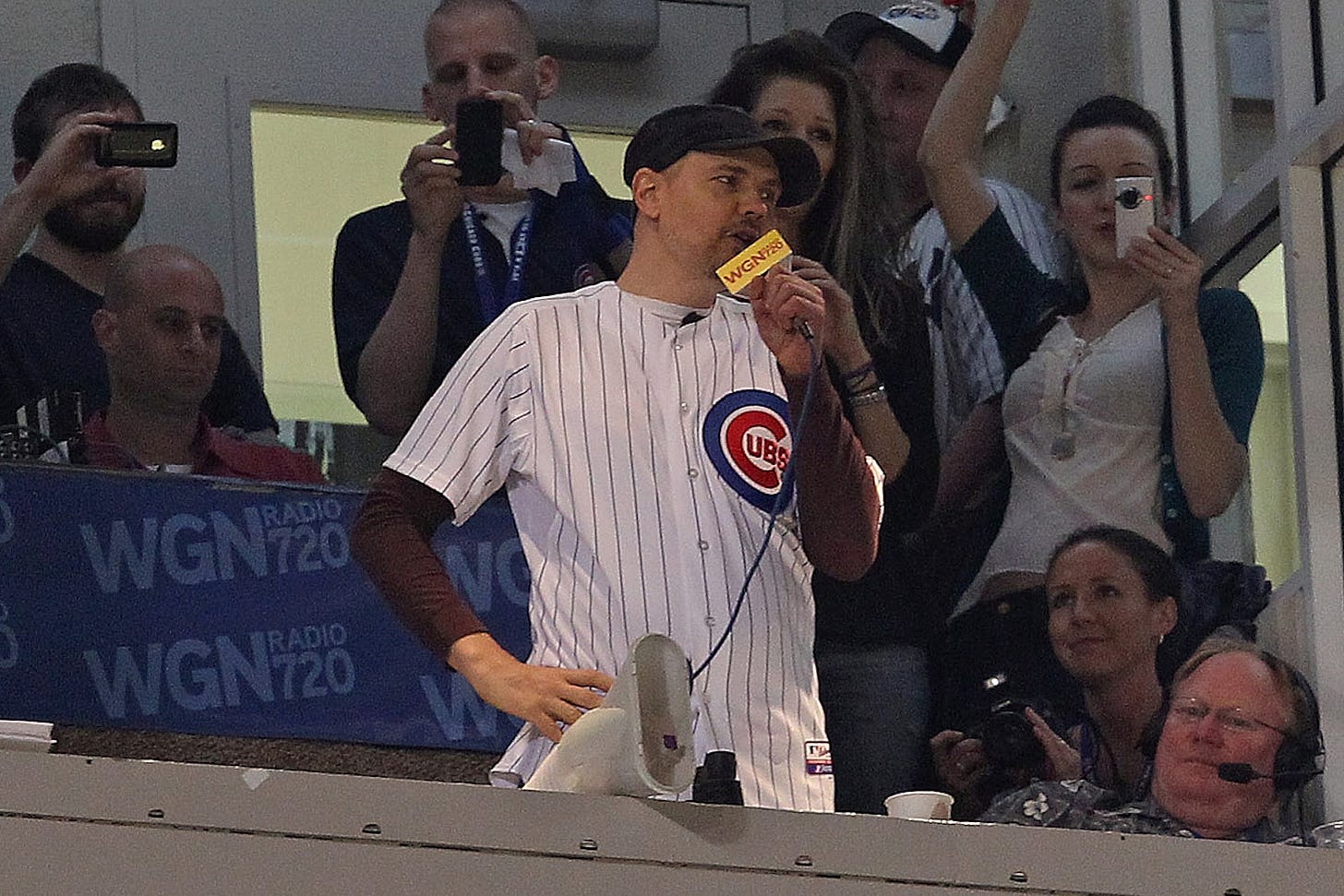

Loving a local band actualized my sense of myself as a person in place and time, connected to a bigger world. Every time I met the Pumpkins was in Chicago. My father took me to the Chicago Guitar Center on November 6, 1998 to buy my first guitar. After, we had lunch at the Chicago Hard Rock Cafe.

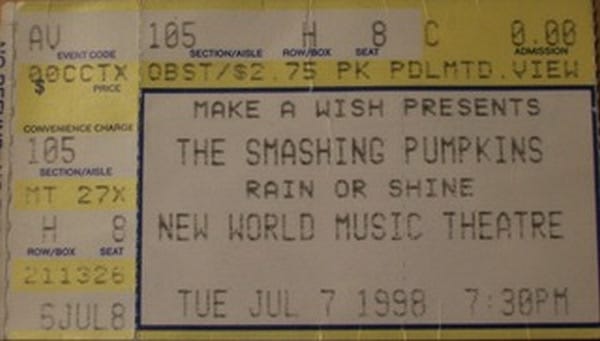

I think it was my father’s idea that we attend my first Pumpkins concert. He procured the tickets and took Moira and I. I remember him explaining the show’s change of venues, per SPCodex:

The July 7, 1998 performance was a charity event at the New World Music Theater with fellow Chicago band Cheap Trick serving as the opening act. The show was moved from Soldier Field due to slow sales. The band originally wanted to host a free concert in Chicago's Grant Park, but were denied permission by mayor Richard Daley, who feared that the show might draw 100,000 fans. Daley later declared July 7th “Smashing Pumpkins Day”.

It seemed that belonging to Chicago brought me that much closer to the band. Intertwined us in ineffable fashion. All these years later, I am still thinking and feeling about Chicago, even though I haven’t lived in my hometown since I graduated from high school in 2003.

For many years after I left for college, I affected a part-time residence in my childhood home, spending every lengthy break from school there, a cumulative total of about four months a year until after my first wedding, where I danced with my father to “Tonight, Tonight.” I was almost thirty before I could even approach the idea that I lived somewhere else.

My peers at the universities where I attended college and then graduate school seemed to have fully moved to those cities. They stayed in the summers, did not scramble for subletters. Some didn’t even go home for the winter holidays. My attachment to my original home could feel babyish, the same way the fact that I still called my parents Mommy and Daddy did. But I was fiercely protective of both practices. I didn’t think of my long stints at home as vacations but as return, resumption of my elemental form.

I had wanted more than anything to go to college in New York, and I enjoyed the time I spent there, but there was no question of staying. No matter how much fun and learning I experienced at school, I was always waiting to go back to my white house in its quiet suburb, with its three cats and carpeted stairs and souped-up basement bar, the only home I could remember, the only place I wanted to return.

How beautiful I found it. I believed that everything there belonged to me.

“I didn’t know what to do with all my longing.” — Claire Luchette, Agatha of Little Neon.

I still don’t. So once more I return.

I let my eyes unfocus and feel the journey back from O’Hare, up River Road to North Avenue, through lush green summer and bare cold winter. Deer in the parkland at the side of the road, a frozen river beneath a low bridge. Russell’s BBQ appears as a beacon when we reach River Forest. That melancholy promise that again I can return once again thrums in my chest, proven, paid. I can pick up where I left off. Once more, I have come back, and home is waiting here for me.

Valentine cardinals in our snowy courtyard. Daffodils and tulips and impatiens my dad bought by the flat and planted in our front lawn. The blooming magnolia tree inset into the half-moon in our cobbled driveway. Ambient cicada buzz in the trees above the backyard, where lilies of the valley bloomed on warm, humid days just before summer. Halloween season, gold-glowing windows, chill nights. At the time of my birthday, high clear mornings, early evenings, driving west or south to someone else’s spare living room, east to the city, where the lake waits like an eye.

City of my birth in me always as cold wind in my face, bright winter light beaming down, the Buckingham Fountain turned off for the winter. Riding the El into the city in the summer, sticky air and possibility, the buzz of side streets when I walked from the station to where I was going. Sitting on the train reading T.S. Eliot out loud to my friend. Commuting to Milio’s at Clark and Belmont, where my hairstylist Vlad’s business card said Hairdresser on fire. How is it possible I had so much freedom?

I remember the winter of 2000 in one sweater—a wide black ribbed turtleneck from French Connection—and one nighttime journey up to Evanston, where David played some concert on the Northwestern campus with a harpist who drove a station wagon just big enough for her and her instrument. After we went to a party at her apartment where everyone was a decade or more older than us. I can just barely bring back that evening in that space, amongst those people. We drank something. Smoked pot. I invent here a flourish of hummus to make it less louche.

David drove my family’s Saab, always David and not me—I would not be a comfortable driver until my mid-twenties, after my whole life in New York, when Los Angeles required it of me. He drove stoned more often than I want to admit. Now I automatically pivot into a parent subjectivity, the terror of two young people hurtling through the night, riding an intoxicated edge. But back then it was just reality. What we were doing, what was happening. I trusted him. I felt safe. We got back to David’s mom’s house very late and slept until one the next day and then we went to Leona’s on Madison for deep bowls of pasta.

That was also the winter I went to see Mulholland Dr. at the Landmark's Century Centre Cinema on the north side. My friend Ted had driven us in his van. He had a big black book of CDs ripped from the library. Sibelius was a favorite. As we drove out after, stunned, Ted put Pet Sounds on. “I think we all earned this,” he said.

Chicago Chicago. Iwan Ries, the tobacconist in the Loop I liked to visit on my way to the train home from the video art class I took at the Art Institute the summer before senior year, where I bought Shepherd’s Hotel cigarettes and participated in cognac tastings. That summer I discovered a world of daytime restaurants on the second floor of office buildings on Wabash and on State, places that served the employees of jewelers and law practices matzo ball soup and club sandwiches in rooms above the street. Quiet bustling private lunch worlds. Is it possible these places still exist? They seem impossibly quaint to me now. Dreamed up by Hayao Miyazaki.

After David went to college a year before me, all I wanted to do on weekends was travel to farflung neighborhoods and try new restaurants. I had no idea what to do with the mounds of whiskered raw shrimp and bundles of beef at the Korean barbecue, tried cooking them whole on my in-table brazier until a waitress took pity on me and came over with a pair of scissors. I took my friends to an African restaurant once, a great success, and was obscurely hurt when it became a favorite they returned to without me. Once, in autumn, my mother took a friend and I to eat coq au vin in a room so dimly lit the night itself seemed a reduced brown sauce, a small French place I remember as inside a sort of cave, under an overpass, trees full of dead leaves pressed against the windows.

The brisk churn of the seasons. The quick passage of the warm days I longed for into interminable darkening fall and iron winter. What a thrill to ride the Skokie Swift, the yellow line, out to a furthest edge of the CTA, eat at a middling diner there, come back again. I spent hours on the train, watching the city pass me in bright pictures. Textures of light. Dioramas of my life. I didn’t know then that I was not the only writer to have felt things on Chicago public transit. Later, in short stories that became creative lodestars, I would find my train moments reflected back to me.

Three pitch mornings, before dawn, when my mom drove me to Wicker Park to board a bus with other teenagers from Young Chicago Authors to a writing festival in Whitewater, Wisconsin. A fall evening I brought my family to the Indian neighborhood I’d discovered on a field trip so that we could eat dosas in a bright, bustling restaurant. The summer day I walked in the beaming heat from the blue line to the Fireside Bowl, a bowling alley cum punk venue where bands performed in the corner away from the dark lanes where mushrooms grew. Cold nights I caught rides to concerts in the city and then took taxis home, giving the drivers directions to River Forest.

One day I visited Pullman, the remains of the town built by and for the titular porters on the deep South Side and invaded by the Army when they went on strike. I came home through a driving rainstorm to find the front door to our house wide open, the power out, my mother pacing strong and warm in a house lit by candlelight, waiting for me.

Always I was coming home. To my house. To my mother.

The best way to capture the feeling of living here for so long has to do with observing the sunrises in the kitchen and the sunsets during dinner facing the back garden. There is a feeling of being centered and protected by looking out at these daily events and observing the gardens and wildlife that visit them hourly. The trees stand in a guardian fashion- the long sheltering branches of the locusts in front and backyard- the perches for the black crows at the very top of our old trees, landings for of all the colorful birds to observe in the courtyard as you prepare meals in the kitchen- the front and backyards are a race track for the rabbits and squirrels patrolling the grounds. And the deer trail between our house- and the [neighbors]- reminds you of living near deep woods- and ancient pathways.

— From my mother’s remembrance of our life in our house, included in the time capsule we buried in the backyard before moving out.

Several years ago I dreamed that I was dropping off my child—it was a daughter—at Concordia University, one of the two colleges within walking distance of my childhood home, to begin her freshman year. I helped her move into her dorm room, took her to dinner, walked around campus with her. That night I slept in a hotel. The house was gone. It had been sold. I didn’t live there anymore. Even after I woke, I was overcome by the sorrow of being so close to my house but not able to stay there.

When I had the dream, my family still owned the house. For thirty-two years, from 1986 to 2018, it was the locus around which our lives coalesced and spun. Where we convened and where we left from. What did I think—that we would live there forever? That it would always be ours?

Yes, I did. Because it was my childhood place I believed in it with a child’s fervor. If I conceptualized of a future in which my parents could not be its custodians—which I did not—I suppose I assumed that I would take over as owner of the house. I perceived no conflict between this goal and the others I held, of living in New York and Los Angeles, of writing books and earning advanced degrees and working wherever the academic job market took me. Of course we would still have the house. Our house was my ontological center. Having it explained who I was.

The other night I went for a walk with my husband and our baby. While most of the country has been untenably cold this week, L.A. enjoyed a very warm Christmas. The weather that night reminded me of a specific kind of Chicago weather, the feeling of a fall evening just before the cold begins.

“You do not get to keep what is sweetest to you; you only get to remember it from the vantage point of having lost it.” — Alexis Schaitkin, Elsewhere.

Now when I look at pictures of our life in our house I can perceive it as in the past. Its presence has ended. The gnashing terror of loss has receded somewhat. I can see it as never before.

On the Spin list “Every Smashing Pumpkins Song, Ranked,” “Once Upon A Time” is number forty-one.

The Pumpkins were essentially starring in their own fairytale for much of the ’90s, but Billy Corgan knew it couldn’t last, and he was determined to write his own ending with Adore. “Time” was gently indicative of the band’s retreat from the Alternative Nation limelight, a 3/4-time ballad that swayed much more than it rocked, sounding less like the soundtrack to America’s youth than the soundtrack to Shakespeare in Love. “Once upon a time in my life,” whimpers Billy, and it’s clear he knows it’s already over.

When my mother was diagnosed with cancer, I indulged in a maudlin fantasy in which, although she had already begun living in a nearby apartment to escape the stress of clearing the house to ready it for sale, she would ask to return to the house to die in her bedroom, in her bed. I couldn’t get this Grand Guignol out of my head, even though it never came to pass.. But when the house sold the next year, we believed her to be in remission. When she died the house had belonged to another family for over a year, and although she was moved many times in the last weeks of her life, from hospital to rehabilitation center to desultory skilled-nursing facility and finally back to the hospital again, she never returned to any home.

Mother, I hope you know

That I miss you so

Time has ravaged on my soul

To wipe a mother's tears grown cold

Sometimes melodrama is earned.

I look at a map. I know it still. Where to go. How to get there. I am there still. It is in me still.

Thank you for reading! This is the fifth of sixteen installments of Adoration Revisited, which will be released every Friday between December 2, 2022 and March 17, 2023. If you enjoy my newsletter, I’d be honored if you share it with your friends. And I’m always interested to hear about your obsessions and memories.

Well, of course, you can go home again, and again, building that powerful place with words, memory, emotions. I love that your mom created a time capsule. Not realizing exactly how it might be re-discovered. Thank you for inviting readers along for this journey.